Photo by Alex Knight

When I got my start in journalism -- all the way back in 1994 -- things were different.

There were newspapers, for one thing. Actual printed paper, often printed locally, at great effort and expense. My first newspaper, the Marion Country Record, still had lead bars sitting around in a back room, from the hot type days. I have one in my dresser drawer at home.

The Record was a weekly paper. The production of it was inescapably a physical process: We wrote stories on computers that were barely more than typewriters. After editing -- I'd deliver the story to my editor on a hard disk -- the copy would be printed up in a single column format, cut up, and then affixed to a page with other stories. (We shot photos on film, which was developed and printed in a dark room.) It was laborious and also joyous. On Tuesday afternoons, the tiny newsroom was filled with the smell of hot wax and the sounds of Bill Meyer -- a veteran of the Battle of the Bulge -- piecing his newspaper together with scissors in hand and a song on his lips.

I didn't expect it to last forever. But I also didn't anticipate what came next.

The internet, of course.

In the course of my career, I have been paid not just to write and occasionally take pictures, but to podcast, produce videos and live-tweet my way through major events. Somewhere along the line, paper became an afterthought. For most of the last 15 years or so -- half my career -- the vast majority of my work has been exclusively digital, or at the very least with print as a secondary concern. I'm wistful about losing the old ways, but I'm also grateful to have a career in journalism. The times have changed, and I have changed with them -- repeatedly. I have done everything I know how to avoid being the proverbial buggy whip manufacturer.

But, hoo boy, ChatGPT, I don't know.

You've hopefully heard about the AI tool that generates text in response to prompts. I certainly have. But I have also avoided reading or listening to too much about it. "ChatGPT" is actually a muted term on my Twitter account, thanks to the obsessive posts by many other journalists -- some of them playing with the tool as a toy of sorts to see what sort of clever thing they do, others publicly worrying about what it means for the future of our profession.

It just kind of fills me with dread. Am I going to be replaced by a robot? I hope not! But also: Possibly!

So: I'm just not paying close attention. I don't read the stories. I haven't played with the tool. I'm just avoiding all of it. There are too many things to worry about. And I sort of have a tendency to worry about all of them.

That strategy probably won't work forever, of course.

What I am hoping happens is this: That AI tools end up helping journalists improve their product, instead of displacing them -- sort of the way Google's search engine suddenly made everybody a much better reporter circa 2000 or so.

And hopefully, as it becomes clear how that happens, I'll be ready to meet the moment. I was never an early adopter -- always the second wave of Twitter and podcasts and the like. That slow-to-innovate part of me has helped me avoid spending too much time on things that didn't last (Google Buzz, anyone?) while still allowing me to adapt when the time came.

But it's also possible that this is going to be the moment that passes me by. It happens to everybody sooner or later. I turn 50 in a couple of weeks, so there’s some midlife crisis stuff probably at play here. I'd like to think I've still got a lot of good work in me. Better, deeper work, even. But I also know that most of the people who entered journalism with me back in the mid-90s have moved onto other, usually more lucrative things -- sometimes by choice, but not always.

I don't want to be useless quite yet.

What I'm reading

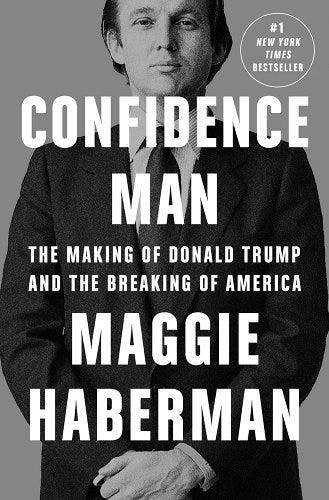

Confidence Man: The Making of Donald Trump and the Breaking of America: I'm not a Maggie Haberman hater like so many people seem to be. People grumble about access reporting, but I think access reporting has its uses -- as long as you're not relying on it exclusively, and as long as you're not captured by the sources. I don't think Haberman has been captured by Trump.

So my critique of this book is not "there goes Maggie again, propping up Donald's corruption." It's that it's ... stale. Granted, I'm reading it months after it came out, but I doubt I'd have a different take if I'd read it back in October. Haberman does a good job looking at Trump's early career. But there's something missing and almost airless about the way she depicts his presidential years -- a sense of the stakes, that Trump's mishandling of the pandemic and cruelty to immigrant families and decisions to pit us all against each other all of the time had stakes out in the real world. Instead, it augments Trump's well-known narcissism by depicting the world pretty much exclusively through the eyes of him and his close associates.

Which wouldn't be so bad, except we've already heard almost all of what is in this book. There's no deep insight or grand revelations. Haberman already put all that stuff into her New York Times reporting. That's a better place to read her than this book.

One more thing

I've been inconsistent about posting to Substack, and have at times overpromised what I'll deliver here. (Hey: It's free.) But I'm going to try to post once a week, probably on Friday or Saturday mornings -- depending on my schedule -- going forward. Unless I don't. But probably.

I relate to this so much, Joel. I'm 54, and I also have memories of printing out stories and editorials and art on sticky paper, using scalpels to cut and fit the stories into the pages as we laid them out on the lighted, glass board. The early days of Pagemaker and all the rest. I met my wife on those campus newspapers. I decided to forgo journalism for academia, and I've been lucky enough to make a career out of it...and now I worry about how advances in AI are going to make it impossible for me to rely upon the writing assignments I've always relied upon. But as you say, there are too many things to worry about...and so I'm just not paying close attention either. I hoping that I'll be able to adapt whenever the moment of adaptation becomes unavoidable, but until then, I'm purposefully not imagining just what that adaptation might be.